Scorsese On LaserDisc

Kyle Matthies continues his themed reviews series with a selection of four Martin Scorsese films

Written by Kyle Matthies

When I was program director at the Grand Berry Theater, one of the series I attempted to implement was an “auteur series” where each month I would select a director, actor, or other above the line creative and showcase four films that help give an impression of who they are as an artist and how they have evolved over time. I only got to do one month’s worth of the series before the theater’s doors closed, but I at least made sure it was a good one. I partnered with Dr. Colin Tait from TCU to show four movies featuring the combined talent of one of cinema’s most iconic partnerships, Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. In case you are curious, those four films were Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas, a great lineup that was an honor to watch with a crowd.

So with me beginning this writing project, and with Scorsese up for his 10th(!) nomination for best director at the Academy Awards this year, it seemed too perfect for the first director whose work I examined to be anyone other than Martin Scorsese. But with a filmography as vast as his, choosing what movies to watch and write about would be a challenge…or so I thought. As one of Fort Worth’s biggest collectors of LaserDiscs (by virtue of a lack of competition) I took a look at which of his movies I own on LaserDisc and was pleasantly surprised at how well they work to show off his range as a director. There has been an upswing in detractors against Scorsese in the wake of his comments a few years ago deriding Marvel movies, and labeling him as a “mob movie” director. While he has directed a few pics that fit in that category, using that as a blanket label to describe him is wildly inaccurate, and I hope these four will help demonstrate that. All four selected movies differ in tone and setting, as well as in cast and just about every notable distinction, making them a perfect window into seeing what truly describes a Scorsese picture. There is also a genuine reason to watch these movies on LaserDisc as Scorsese has a very notable connection to the medium- the final feature film ever released on LaserDisc in the United States was a Scorsese picture, his aptly named 1999 film Bringing Out the Dead. For the sake of this series, we are going to be taking a look at After Hours, The Last Temptation of Christ, Cape Fear, and The Age of Innocence, in the arbitrary order that I watched them.

Cape Fear (1991)

As an homage to the previously mentioned Scorsese and De Niro month I did at the Grand Berry, it seemed only natural to start with the only De Niro collaboration. I had not previously watched this movie but I had a level of familiarity with it. We actually used the iconic scene of De Niro smoking a cigar in a movie theater as part of the Grand Berry’s pre-show video, and I was aware of the film’s status as a remake.

Coincidentally, I actually bought the original on LaserDisc the same time I bought this one, but I have not seen it yet. What I was not expecting was how much of this film’s DNA comes down to it being a remake. Nearly every aspect of the film comes from a place of deep reverence for the original film and the film-making techniques of its time. For instance, the film uses Bernard Herrman’s score from the original 1962 picture, but adapted by Elmer Bernstein to fit the tone and pacing of this new imagining of the story.

This picture is a lot like that newly adapted score, it takes what came before and attempts to modify it in such a way that it has modern sensibilities while still keeping the style of an older film. At times it works, while at others it feels too infatuated with its status as a remake to carve out an identity of its own. The camerawork takes clear inspiration from Hitchcock and other thrillers of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Its fast cuts and crash zooms create a feeling of anxiety, but they also create a nostalgic remembrance of an era of film-making that has long since past, which when juxtaposed with the ‘90s level of excessive violence, is an odd feeling.

Aside from the visual parallels, the film pays even further homage to the original by casting its lead actors in small parts. Both Robert Mitchum and Gregory Peck show up here, with this actually being Peck’s final feature film appearance. Such casting reminds me of modern legacy sequels, where the original actors show up to “give their blessing” in a way that tells the audience this is an acceptable thing and not an exploitative cash grab to make more money off of an existing property. Of course, this is a remake and not a legacy sequel, but in an odd, indescribable way it has a lot of that same energy.

That’s not to say there’s nothing added to the film. Robert De Niro is great in his role as Max Cady, the charismatic ex-con out for revenge. He is chewing up the scenery in a way which is never not entertaining. I’m not a big Nick Nolte fan, and this did not change that for me. Nolte works best for me when he is playing a flawed man, which on paper his character is, but in practice, his one flaw came from a place of desiring to do good, which made him not work well for me. I think his character should’ve come off as more broken from the start, but by making all of his inner turmoil come from Cady and not from within, I believe a bit of potential was missed.

Missed potential is honestly what a lot of this movie amounts to for me. It’s a good, certainly enjoyable movie, but by sticking too hard to what came before, it lacks an identity for itself, which ultimately holds it back from being anything more than a fun distraction. It’s worth a watch, sure, but it doesn’t stand out enough to be anything too special.

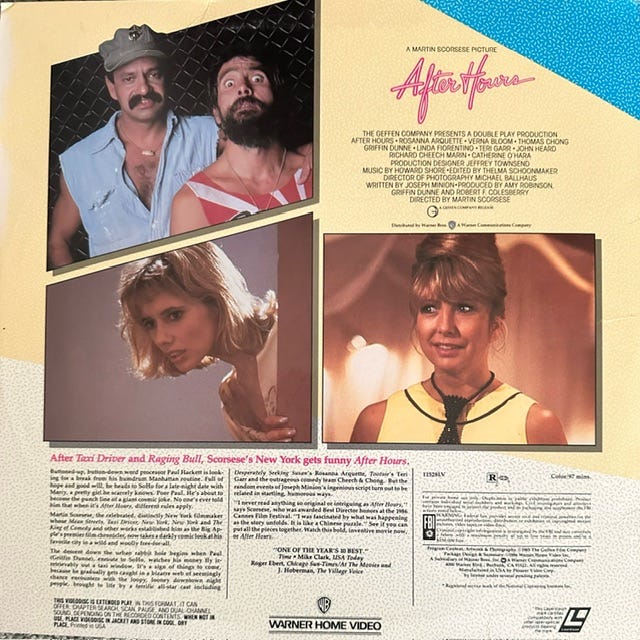

After Hours (1985)

As this film focuses on a man having a legendarily long night after work one day, I figured the only way to properly experience After Hours was to watch it after I got off a nine hour shift at 1AM. It was just before two in the morning when I hit play and, honestly, I can’t think of a better way to have experienced this. It certainly helps that this movie is only a little over 90 minutes, a rarity when it comes to Martin Scorsese.

After Hours stands out as an odd entry the Scorsese filmography, and not just with its reasonable runtime. It is, to date, the last film that Scorsese made that is not either an adaptation or a biopic. While its set in his favorite setting of New York City, its focus on a yuppie navigating through a rough Soho night feels more like Woody Allen subject matter than Martin Scorsese. This is only furthered by the decision to make it a comedy, a genre that Scorsese is not known for, but is no less effective compared to his other movies. It’s less of a laugh-out-loud at all the funny jokes kind of comedy and more of a “it’s a funny situation that’s enjoyable to see how it unfolds” kind of comedy if that makes any sense. As if God himself is laughing at the misfortune he is unleashing on poor Paul Hackett, who wants nothing more than to go home but continues to be unable to catch a single break. It’s a compounding comedy where every 10 minutes the situation has found a way to amplify, and things cannot stop escalating.

One aspect of film-making that makes this stand out among Scorsese’s filmography is the casting. Of the main cast, only Verna Bloom worked with Scorsese again, appearing as Mother Mary in The Last Temptation of Christ. Scorsese regulars Victor Argo and Dick Miller also appear in small roles, but that’s it for repeat actors. So who does it star? The lead role is played by Griffin Dunne, an actor I primarily recognize as playing the prematurely deceased friend in An American Werewolf in London. Aside from him you have; Rosanna Arquette (Desperately Seeking Susan), Teri Garr (Tootsie), a mini prelude to Home Alone with Catharine O’Hara and John Heard, and Cheech & Chong, of course.

Its through the film-making itself that After Hours is comparable to other works in the Scorsese library. Like all of his films from the ‘80s to now, it was edited by Thelma Schoonmaker, and while her editing style was different in Cape Fear, the way this film is edited is very similar to the next two movies we’re going to look at. Michael Ballhaus is the cinematographer here, and he will do the cinematography for five total Scorsese movies, including The Last Temptation of Christ and The Age of Innocence. Ballhaus and Schoonmaker make the backbone of Scorsese’s visual style in all of these movies. Each possesses similar camerawork and a natural, flowing editing style that uses the momentum of the characters as the driving force between cuts. Its that energy that propels After Hours and makes the unrelenting cavalcade of poor luck that befalls Paul Hackett so engaging to watch.

If I were to lay down any criticism for After Hours, I’d have to voice my dismay for how quickly everything wraps up at the end. This is easily one of my favorite movies Scorsese has ever released, but I must admit that the ending does not feel earned. Everything else in this movie is so intricately built, so to have an ending come out of nowhere in the last 45 seconds before the credits roll feels under cooked. It’s just too bad that adding maybe 1 or 2 minutes is all it would’ve taken to take this to the next level of a flawless movie and they didn’t do that.

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Before we start, I want to briefly state that this was my first experience with the scourge of LaserDiscs everywhere, the horrible sounding dreadful death sentence that is laser rot. Because of this unwanted infestation that has besieged my copy of this movie, the colors were a little off- the most evident distortion being all the shadows coming off green instead of black. It was watchable, but definitely not the way this movie was meant to be seen. The things I put up with out of commitment to a stupid gimmick…

Religion is a major theme of Scorsese’s work. Nearly all of his movies touch upon Catholicism in some way or another. The Age of Innocence, for example, has baptism as a recurring motif, and After Hours relied on heavenly imagery as the basis for its final scene. But in The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese takes his infatuation to the next level by making one of the most interesting movies about Jesus of all time.

As the film opens up, the audience is given a text crawl that provides some pertinent information. It tells you that this film is not based upon the Gospels, but rather a novel titled The Last Temptation of Christ which deals with Jesus’ struggles and doubts as he went through his life, unsure of his destiny or how he should act as the son of God. Many of the plot beats here mirror those of the Gospels, but instead of focusing on the actions of Jesus, this movie focuses on how Jesus feels about the world around him and his place in God’s divine plan. It’s a more engaging take on the story which is often told in such a way where Jesus as a person is thrown to the wayside in exchange for a focus on Jesus as an idea. I think Roger Ebert summed it up best when he said this is a film that differs from others that tell the same story by “paying Christ the compliment of taking him and his message seriously, and they have made a film that does not turn him into a garish, emasculated image from a religious postcard.” Indeed, I had to watch my fair share of Jesus movies in my upbringing, and Ebert’s words ring true to me. So many other movies about the life of Christ focus on nothing more than replicating what happens in the Bible, and its beyond refreshing to see a movie where Jesus is an actual character.

Not everyone shares that opinion though, as the film was very controversial upon its release, with many Christians labeling the idea of Jesus not being fully committed to his faith as supremely blasphemous. Judas, likewise, is portrayed in a way that didn’t gel with more fundamentalist audiences. In this film, Judas is perhaps the truest believer of Christ’s message and only “betrays” Christ at the behest of Jesus himself. But the part of the film that garnered the most controversy would be the exceptional third act that must be seen for itself, and I would dare not spoil.

It’s an effective movie that even an nonreligious person like me can still enjoy, so I definitely recommend checking it out. Seeing Willem Dafoe play Jesus is worth the price of admission itself, not to mention a cameo from David Bowie and a great minor performance from the always incredible Harry Dean Stanton.

The Age of Innocence (1993)

The Age of Innocence sees Scorsese returning to New York City, this time focusing on the high society of the 1870s. Romance is another common facet of Scorsese’s work, and while not a major theme of the other films I watched this week, it is the driving force here. Much of The Age of Innocence focuses on the internal struggle inside one wealthy lawyer (Archer) who is expected by his high society connections to remain with his fiancé (May), but he has yearnings for May’s cousin (Countess Olensak) who is also his client. It is a character driven story of full of subtleties, where the characters’ interactions with each other shape the story in organic ways and everything feels authentic. The customs of the time are explored in such a way that the audience can understand them and the weight of their societal expectations are tangible.

Archer is played by the great Daniel Day-Lewis, who is the master of period accurate characters. Through him, all of what occurs feels believable, and the internal turmoil of his character is worn on his face. Even without saying it, his ever changing feelings towards both May and the Countess are evident and followable in such a way that denotes a well-directed movie. Day-Lewis isn’t alone in this either, Michelle Pfeiffer plays the Countess, and also comes off as a conflicted woman who is wrestling with the same unwelcome feelings of lust for Archer, and unsure of how to best proceed without giving in and ruining her already tattered reputation. Winona Ryder was nominated for an Academy Award for her performance as the naïve and innocent May, who is blissfully unaware of Archer’s desire to be with her cousin over her.

An interesting connection between this and Cape Fear is the use of Saul Bass to design the introductory credits sequence. Saul Bass was an iconic graphic designer in Hollywood who designed the credits, logos, and posters for many of the most iconic films in Hollywood history. Seriously, look him up because there is too many great films for me to list here. But this was one of his final works and for this film he designed roses made out of lace which in a clever way exemplifies the themes of delicate sensuality which define The Age of Innocence.

With the Ballhaus cinematography and Schoonmaker editing, this undoubtedly feels like a Scorsese movie, but its setting and tone may make this one more inviting to audiences who don’t quite enjoy the focus on crime and violence that defines much of his other work. The fact that he can make movies that appeal to an audience that would normally not overlap with his usual sensibilities is a true testament to the range that Martin Scorsese has as a filmmaker.