Hyperlocal Man of Mystery: The appeal of Woody Allen

By Kyle Matthies

There was a time when the term cinema was synonymous with Woody Allen, and when his movies were the toast of cinephiles everywhere. His films, released nearly annually between 1971-2017, were perennial contenders at the Academy Awards, and he received the first honorary Palme D’or to add to his accolades. His reputation has diminished in recent years, but I felt inspired to take a look at a few of his movies to see if I can understand why people were so crazy about his films for such a prolonged period of time.

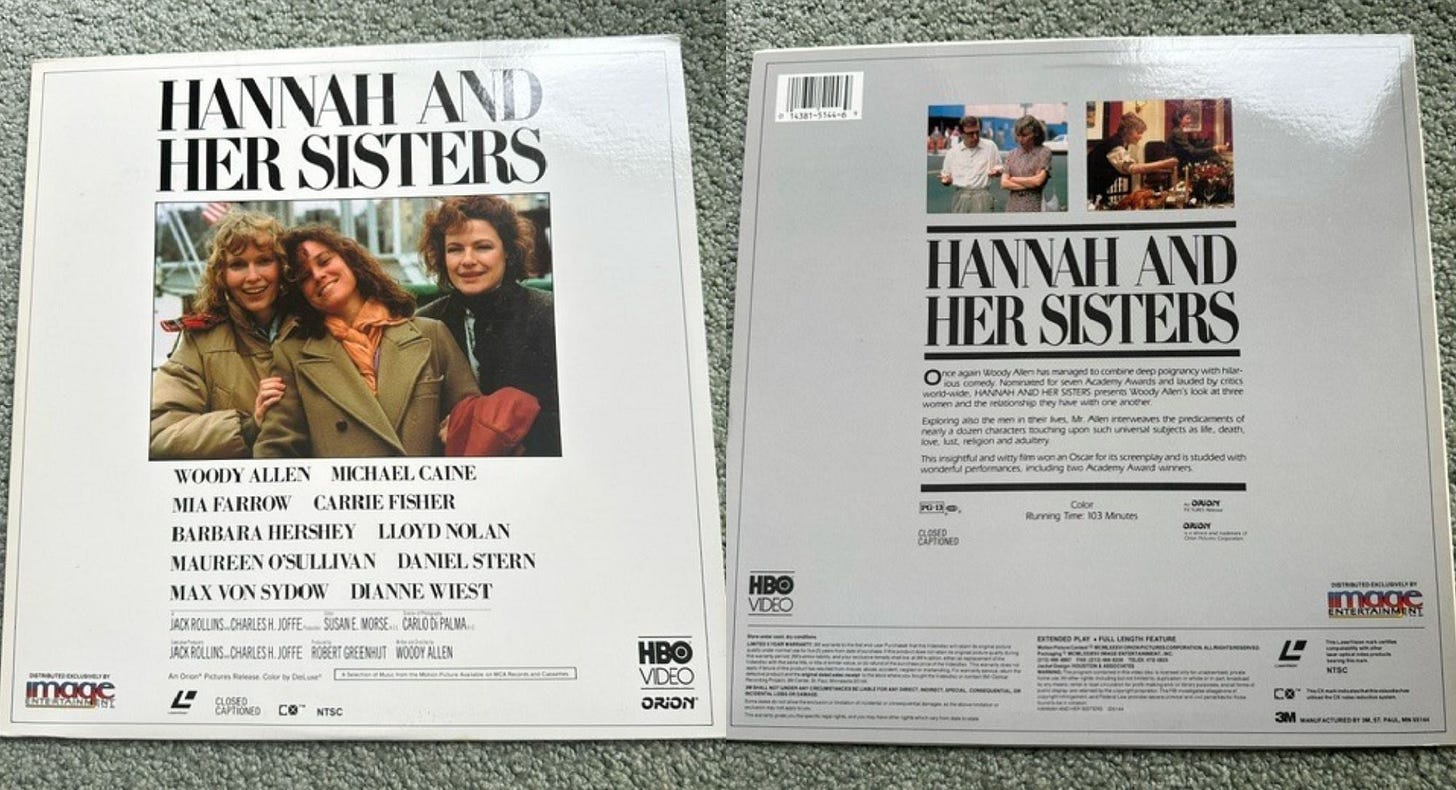

For this endeavor, I pulled out my LaserDisc collection and watched four of his movies that I already owned- Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), Hannah & Her Sisters (1986), and Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993). Instead of writing about each film individually, I am going to write about four aspects that pervade each of these movies and how they might be the key to finally understanding Woody’s movies.

It Ain’t Woody’s New York Anymore

It’s not a revelation to say that Woody Allen loves New York. All four of the movies I looked at are set in the Big Apple, as if titles such as Manhattan and Manhattan Murder Mystery weren’t already clues. What really sets his portrayal of the city apart is in how nostalgic the tone is. It’s as if Allen knew that the city he loved would not always stay this way and so he took the necessary action to capture a lasting snapshot of the city on celluloid, allowing repeated visits to a world that no longer exists. It’s telling that I’ve only been to New York once as a small child yet I can feel warmly towards the nostalgia presented here, so I can only imagine how anyone with an emotional connection to New York would feel towards these flicks.

This sense of nostalgia comes from how Woody’s films capture the sights, sounds, and scenes of the big city. Annie Hall and Manhattan use the talent of cinematographer Gordon Willis (The Godfather trilogy, All the President’s Men) to create a moving portrait of the city. Annie Hall’s lengthy shots and Manhattan’s black-and-white anamorphic widescreen presentation (which my sources say looks a lot better when not watched on a 480p LaserDisc) pair well together to show different ways of looking at the same city. Carlo di Palma’s cinematography in Hannah & Her Sisters and Manhattan Murder Mystery gives a more grounded, street level view compared to Willis’ love of aerial shots, but this compliments their respective movies. The street level focus of the later movies works to better emphasize the characters and their relationship with the city around them.

There’s always music in the air in Woody’s New York. Jazz scores set the mood of a city that encourages freedom and self-expression. These soundtracks are the glue that holds the movie together, proving to be just as pivotal to the setting as the visuals of the city. Nightclubs, cafes, and the streets themselves are alive with the sounds of jazz, injecting an aura of New York authenticity that adds tremendously to these films. There’s a sense that Woody’s New York is a vibrant place to live, and it’s through this element that these movies sink into your psyche. I could watch any of these again just for a chance to revisit this version of the city that only can exist on the silver screen.

A Pattern of Relationships

There is, of course, more to Woody Allen’s movies than just the setting, and by that I mean we need to talk about the relationships. Each of the four movies I watched had one or more tumultuous romances at the heart of the story, and the lessons learned from these provide the themes for their respective films. I’m not going to discuss some of the odd similarities present in these relationships such as three films having Woody’s partner leave him for a college professor, but rather how each film differs in their portrayal of human relationships.

Annie Hall is a movie that seeks to answer why humans go through the difficult process of falling in love despite the inevitably painful ending. The relationship between the titular Annie Hall (Diane Keaton) and Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) is compared to relationships in Alvy’s past as he stacks up his feelings towards Annie against his past loves. While primarily played for comedy, the film’s use of voice-over narration and fourth-wall breaking allows for some poignant insight into the nature of love that seamlessly slides between the jokes. Together they have a romance that must have felt modern and new when released in 1977, and even today has some lessons to impart to the audience.

Manhattan uses the same leads, Woody Allen and Diane Keaton, to tell a different story of love. This time, Allen plays Isaac Davis, a TV writer who is dating a 17 year old girl (yeah, I know) after his wife left him for another woman. It’s a story of settling vs. fighting for who you truly love. His younger lover is infatuated with him, but Isaac’s heart starts yearning for a more honest connection, leading him to begin an affair with his best friend’s mistress, Mary (Keaton). The theme of following your heart works on all characters as Isaac, Mary, and Isaac’s younger girlfriend all change their minds as to who they want to be with several times before they can accept that they must do what’s right for the heart.

Hannah & Her Sisters surely has the most relationships at the heart of the film, both platonic and romantic. As the title implies, there is a sisterly relationship at the heart of the story, exploring how Hannah (Mia Farrow) and her two sisters (Barbara Hershey & Dianne Wiest) support each other as well as their parents is a nice relief from their otherwise disastrous love lives. Together they have to deal with a husband who begins to prefer one sister over his bride (Michael Caine), a stagnant long-term relationship with a reclusive older artist (Max Von Sydow), and a hypochondriac ex-husband (Allen) who inadvertently finds himself back in the sisters’ lives after a chance encounter. It’s the kind of story that uses its large cast and their interactions to provide its message. There is no one relationship that defines a person, but instead it’s their interactions with the people around them where meaning starts to be found.

Manhattan Murder Mystery was the newest of the four movies I watched and with it came a more mature lesson to be gleaned from the central relationship. They say that wisdom comes with age, and here we have Woody Allen and Diane Keaton reuniting 16 years after Annie Hall to tell a story that reflects their older age. This time the two play a married couple whose spark has gone out and the magic between them has fizzled. When Keaton becomes convinced their neighbor has murdered his wife, she begins investigating, much to the chagrin of her husband, exemplifying the furthering divide between them. Complicating things are a pair of potential lovers (Anjelica Huston and a particularly charming/flirtatious Alan Alda), each using the murder investigation as a way of getting closer with each of the leads. I actually quite liked how this one ends and, like the others, it can be quite poignant with its messaging in the finale.

A City of Cinema

There’s been a joke for a long time now that if you want to win Oscars, make a movie about movies. While none of these films are about cinema itself, a love of movies is deeply coded into the DNA of Woody Allen’s works and I think that may have a lot to do with why the critics loved him for so long.

On a near constant basis throughout all of these movies, the characters discuss cinema, go to the movies, and the plots themselves reflect of some of the most influential films of yesteryear. For example, look at how outspoken Woody is with his love of Ingmar Bergman. Both Manhattan and Annie Hall feature scenes where Woody takes a date to see a new Bergman movie in theaters, something that Annie Hall takes even further when Woody gets into a spirited debate about the merits of Bergman and Fellini while waiting in line for said movie. Hannah & Her Sisters borrows most of its structure from Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, both films spending three years following one family during a certain festivity (Thanksgiving for Hannah, Christmas for Fanny) and how they evolve over that time. This post-modern way of paying homage to a film by borrowing and subverting the structure is exactly the kind of thing that film critics and cinephiles eat up, so it shouldn’t be too surprising to see that Hannah & Her Sisters won the Academy Award for best original screenplay.

Without drawing from Bergman, Manhattan Murder Mystery also exhibits this level of deep cinematic influence. This time Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai is the lucky film, which is mirrored literally and figuratively in the final act. Both films end in shootouts behind a movie theater screen, in a room full of mirrors. In Manhattan Murder Mystery, that theater is actually playing The Lady From Shanghai, so the seen being emulated is visible to the characters and audience during the matching fight. Is it subtle? No. But yet it works as a direct homage in a film that has never played itself too seriously.

Conclusion

After watching these films, I do feel like I at least am starting to understand the appeal that Allen’s films held for the film world over multiple decades. Annie Hall was the only one of the four movies that I would say I really loved, but each has their own merits and a distinct voice that builds to create a style that is easy to imitate but difficult to authentically replicate. If you love New York, movies, and intricate human relationships, then Woody Allen may be right up your alley, which apparently was enough for the film-going audiences of the 1970s-2000s.